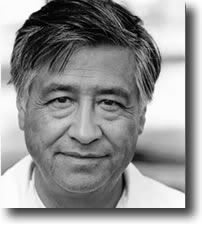

Note: Msgr. Boyle is a retired priest of the Diocese of San Jose, tireless advocate for the poor, and member of the Diocesan Human Concerns Commission. He has generously offered to share these recollections of his experiences with Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers' Movement. by Monsignor Eugene BoyleIn 1962, Chavez began to organize farm workers in Delano. Almost from the beginning the church, encouraged by Cesar, was at his side supporting the movement in a variety of ways. First, the California Migrant Ministry of the Protestant church and, then, a number of Catholic priests joined the initial organizing efforts.

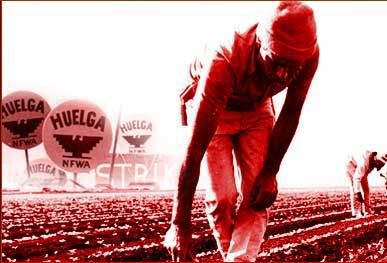

In the fall of 1965, quoting Pope Leo XIII, Chavez persuaded the members of his fledgling Farm Worker Association (FWA) to go out on strike against the grape growers. During its first days Chavez appealed to the strikebreakers through a bullhorn from a light aircraft flown over the fields by a priest pilot, the late Keith Kenny of Sacramento.

Veteran labor reporters for California's metropolitan newspapers predicted that the strike could not possibly be successful. The National Labor Relations Act excluded farm workers from protection in efforts to achieve collective bargaining. So it came down to a naked test of strength. How could the strength of impoverished farm workers compete with that of multimillion-dollar agribusiness? How long can a union adequately picket 10,000 acres?

In mid-December the quest for new and more effective directions produced a brilliant inspiration - a consumer boycott against the products of Schenley industries, one of the two largest Delano firms. Here again the realization of this truly inspired concept depended largely on the churches and their networks countrywide. NFWA representatives dispatched to most of the major cities in the country to organize and coordinate local boycott groups found their most hospitable reception in the churches.

The fruitful wedding of religious faith with the struggle to establish a viable union for farm workers was never so evident as in the march from Delano to Sacramento in Lent of 1966. It was Cesar Chavez's own idea: a march to the state capitol in Sacramento to petition Governor Pat Brown to do something about collective bargaining rights for farm workers. But it was more than a march; it was a peregrination, a religious pilgrimage, and a way of the cross of sacrifice and penitence. A barefoot campesino carrying a plain wooden cross and another carrying the banner of Our Lady of Guadalupe marched in the lead.

It was during this march, when I connected with it for a day, that I first met Cesar. When I joined him he was walking with a cane, his feet burning with blisters, one of his legs severely swollen. I hesitated to disturb him. But he greeted me graciously, obviously pleased that a priest had linked with the march, his dark, fascinating eyes capturing me forever. He spoke of the pilgrimage as a way of spiritual training for himself and the other farm workers to prevail in the long, long struggle which by this time was all too evident.

On later reflection I saw the Spirit-driven Jesus of Luke's gospel steadfastly making his way to Jerusalem, consumed by compassion for the anguished he met on the way and expending his all to alleviate their pain.

On April 6, Wednesday of Holy Week, the march came to an abrupt halt as the participants stopped to applaud and cheer the good news that seemed heaven-sent: The major grower had agreed to recognize NFWA and to negotiate a contract covering all his field workers in the Delano area. On the following day, Holy Thursday, there was even more astounding news. Another major grower, infamous for his implacable opposition to farm unions, agreed to hold union elections.

At high noon on Easter Sunday, with the banner of Our Lady of Guadalupe and the cross prominently displayed, the peregrination reached its triumphant conclusion at the state capitol in Sacramento. Ten thousand people gathered on the steps and the adjacent lawns in what can only be adequately described as a religious revival; praying and pledging continued support for the cause of justice for farm workers.

For the next two years, supported solely by the national grape boycott, Cesar Chavez and the NFWA settled into the grueling task of wresting from reluctant growers union representation elections, recognition and contract negotiations. Given the absence of labor law, the unconscionable intrusion of the Teamster Union into the fields and the union's commitment to nonviolence, the number of contracts the NFWA achieved was remarkable. But there were some major growers whose resistance was obdurate.

There came a time in early 1968 when Chavez feared he was in danger of losing a good part of the workers. Because if an apparent lack of progress after more than two years of striking, and a sudden increase in violence against the union, there were those who felt that the time had come to overcome violence by violence.

In the Lent of that year, to smother the rage smoldering in the ranks and to unify and redirect the workers to the nonviolent pursuit of justice, Chavez, inspired by the teaching, as he said, of Jesus Christ and Mahatma Gandhi, went on a penitential fast which he observed for twenty-five days.

On the day he broke the fast, Chavez, too weak to do so himself, had an aide read a statement he had prepared. It was the gospel according to Cesar: "Our lives are really all that belong to us... only by giving our lives do we find life. I am convinced that the truest act of courage, the strongest act of manliness, is to sacrifice ourselves for others in a totally nonviolent struggle for justice. To be a man is to suffer for others. God help us be men."

I was the principal concelebrant of the Mass the day Cesar broke his fast. Our sanctuary was a flatbed truck on the Forty Acres in Delano, the original headquarters of the union. I still have a photo of myself giving communion to Cesar and Bobbie Kennedy, who was assassinated just two months later.

At their meeting the following year (November 1969), two California bishops - Bishop Hugh Donohoe of Fresno and Archbishop (later Cardinal) Timothy Manning of Los Angeles - urged the conference to offer their services in some way as mediators between the farm workers and the growers. Before the meeting adjourned, the Bishops had formed the Bishops' Ad Hoc Committee on Farm Labor, which included both Californians.

The work of this committee successfully culminated in July of 1970 when the five-year-old grape boycott ended with the historic settlement between the United Farmworkers of America-Afl-CIO and twenty-six grape growers of the San Joaquin Valley. This settlement, together with other agreements in the southern part of the State, brought more than three-quarters of the state's table grape harvest under the collective-bargaining umbrella of the UFW.

Unfortunately, this victory was short-lived. In April of 1973, when the original contracts between the UFW and the growers expired and were up for re-negotiation, the Teamsters Union signed contracts with thirty of the growers without ever meeting with the farm workers they claimed to represent. The battle was again enjoined.

During this crisis, too, the contributions of the Bishop's Committee and other church members to the efforts of the UFW to regain their contracts proved invaluable. Ultimately, for all their money and power the Teamsters could not stand up to the impoverished but inspired and selfless members and officers of the UFW - and their friends. On this occasion the bishops explicitly endorsed both the table grape and lettuce boycott.

In November 1974 the Catholic Bishops of the United States again acknowledged the seriousness of the farm labor problem and reiterated their belief that the urgency for its solution is as grave as ever. "It is a national scandal that at both the federal and state levels sufficient pressure is not being brought to bear on legislators to pass legislation that will be just to all parties. That legislation must assure the farm workers the right to elections by a secret ballot of a union of their own choice."

In November of 1975 the Bishops of the United States issued a different kind of Resolution on Farm Labor. It was an unqualified commendation of Governor Edmond G. Brown, Jr., the state legislature and all others involved for the enactment into law of the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act. "This is the first law ever enacted in any jurisdiction, federal or state, guaranteeing farm workers the right to determine, by secret ballot elections, which union, if any, they want to represent them."

"We call upon all concerned - state officials, growers and union representatives - to cooperate with one another in implementing the spirit as well as the letter of the law.

"It would be a tragedy if the purpose of the law, which holds out such promise for the future of sound labor relations in the agricultural industry, were to be thwarted in practice, for whatever reason."

Within a year of its passage the growers, aided and abetted by a state administration unfriendly to the union aspirations of farm, workers, waged a campaign to "thwart in practice" the legislation. The Agricultural Labor Relations Board, established by the law to oversee its implementation, is practically non-functional. The ALRA, originally intended to assist the collective bargaining endeavors of farm workers, has instead, by its one-sided administration, crippled these efforts to this day.

The United Farm Workers Union - AFL-CIO (UFW/AFL-CIO) is an authentic, American labor union, successfully organizing thousands of farm workers. But, as even its opponents attest, it has always been more than that. Initially led by the Spirit-filled person of Cesar Chavez, and now by his like-spirited successor, Arturo Rodriquez, it has also been, and still is, a movement of total compassion and concern for the exploited farm worker.

The funeral of Cesar Chavez was an overwhelming experience that has no other explanation than the power of the spirit of this great man now unbound. Over 35,000 people were drawn to Delano to form a four mile procession (read: pilgrimage) led by the body of Cesar carried on the shoulders of farm workers and supporters up the rural Garces Highway to the Forty-Acres, the original headquarters of the union.

There a Mass of the Resurrection, at which I was a concelebrant, was celebrated, sacramentally validating the truth of our experience - the spirit of Cesar Chavez lives and will continue to inspire the movement and labor union he founded.

Viva Cesar Chavez! Viva la Causa!For additional information:

Organizations/Websites:

The Cesar E. Chavez Foundation

The United Farmworkers Union

Resources:

"The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers' Movement," VHS, PBS Documentary Film, 1996, see also book based on the film by Susan Ferriss & Ricardo Sandoval, Harcourt, 1997.

"For I Was Hungry and You Gave Me Food: Catholic Reflections on Food, Farmers, and Farmworkers," U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, November 2003

On March 15, the Parish Social Justice Liaisons representing twenty-three parishes came together for a Breakfast Meeting at St. Clare Parish Hall.

On March 15, the Parish Social Justice Liaisons representing twenty-three parishes came together for a Breakfast Meeting at St. Clare Parish Hall.